Updating Oakland’s Memorial Hall for the 21st Century

This year, the Town of Oakland and its signature structure, stately Memorial Hall, both turn 150. Built to honor Oakland’s Civil War dead, Memorial Hall has, at various times, hosted a bank, a post office, a Civil War veterans group, elementary school classes, town offices, the town library, church services, high school graduations, and much more. Now, at its sesquicentennial, the town-owned building needs renovations so that it can continue to serve the residents of Oakland and the surrounding towns.

Back in March 1869, when Oakland was still part of Waterville, the town of Waterville appropriated $2000 to build Civil War memorials. The money was evenly divided between the villages of Waterville and West Waterville, as Oakland was then called. (Oakland separated from Waterville in 1873, and took the name Oakland ten years later.)

In Waterville proper, the funds helped pay for a bronze replica of Martin Milmore’s statue of an ordinary Union soldier. The original “Citizen Soldier” was erected in a Boston cemetery and copies soon appeared in numerous northern cities and towns. That statue still stands in Monument Park at the corner of Park and Elm Streets in downtown Waterville.

In West Waterville, community leaders decided to build a public hall, where the townsfolk could gather for occasions both solemn and celebratory. The West Waterville Soldiers’ Monument Association led the efforts. Plays staged in other local venues were important fundraisers. Construction started in 1870 and finished three years later. By most accounts, the total cost of construction was $12,00, which comes to roughly $280,000 in 2023 dollars.

The hall was designed in the Italian Gothic style by Thomas Silloway (1828 – 1910). A former Universalist minister, Silloway designed over 400 church buildings and various other public edifices in Eastern United States, including the Vermont State House. At the time, it was unusual for structure so grand as Memorial Hall to be erected in a town as small as West Waterville, which had but 1,500 inhabitants when the building was completed.

The principal building material was slate from a quarry on the banks of Messalonskee Stream, near where the Cascade Woolen Mill once stood. The Oakland Historical Society’s website describes the hall’s architecture thus: “The Hall is a masonry structure, built out of stone from a local quarry with brick trim. The gabled entry is flanked by tall sash windows in segmented-arch openings, with mini-gables in the roofline above. The entry section has a steeply pitched gable, with a rounded-arch recess housing a beautiful stained glass rose window at its top. The corners of the entry projection are buttressed, and the building corners exhibit brick quoining.”

In its 150 years, the hall has seen many and varied uses. The western end of the basement was originally occupied by the West Waterville Savings Bank — an empty, granite-walled vault is still there — and the central room became a post office. The eastern part of the basement was a garage for a handtub fire engine. (This 19th-century forerunner of a pumper truck consisted of a metal tank on wheels with a bar running the length of either side. Groups of firefighters, half on each side, would pump their bars up and down, like a seesaw, to make the water shoot out of a hose.)

After the post office moved out, the local chapter of the Grand Army of the Republic, a nationwide organization of Union veterans of the Civil War, moved in. By 1904, the bank was gone, but Oakland moved its town offices into the building, and in 1905, the town’s three-year-old free public library moved in as well. The library remained in the basement of the hall until its current building, one of over 2,500 library buildings built through the generosity of industralist Andrew Carnegie in the U.S. and beyond, opened half a block to the north in 1915.

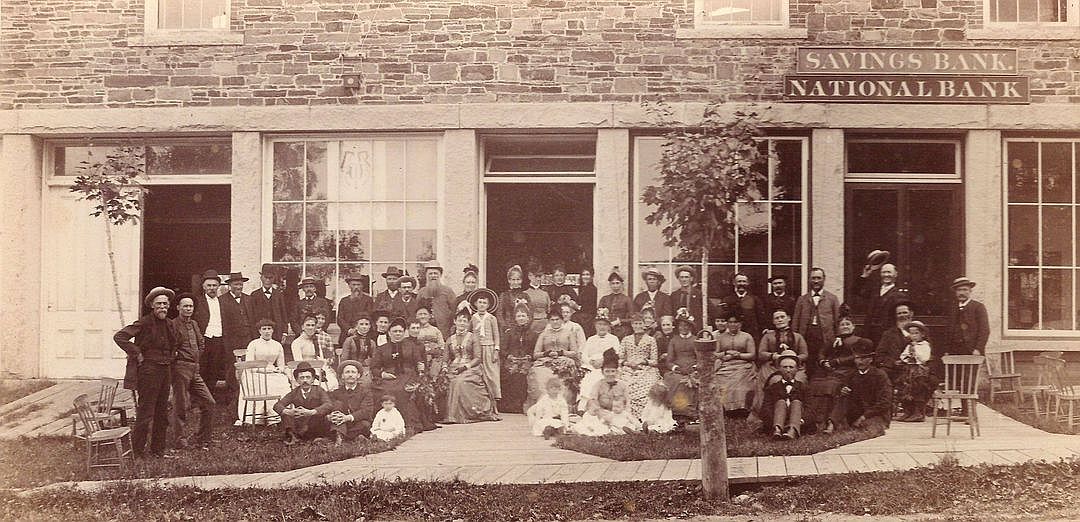

In the early 20th century, the hall was also used for 1st and 2nd grade classes and for Catholic worship. Until the early 1990s, it was a polling place. The auditorium on the main floor, which by one account could seat 350 people, was used for town meetings, high school graduations, plays, and various other meetings and receptions, public and private. (See photos below.) Nowadays, the building is used primarily by a local dance school.

The restoration of Memorial Hall is a project of the Oakland Area Historical Society and the Town of Oakland’s Memorial Hall Committee. The first phase, which is expected to cost around $500,000, is repointing the exterior stones and repairing the granite front steps and a granite retaining wall. This work will take place next year. Later phases, which will take place as funding becomes available, will include adding a sprinkler system, an elevator, and handicapped-accessible restrooms in order to bring the building into compliance with current fire safety codes and the Americans with Disabilities Act.

At an open house in the hall in May, five groups of architecture students from the University of Maine at Augusta presented design concepts to update the building while retaining its historic character. Each of the five plans included an elevator inside the building and a wheelchair ramp outside. A professional architect will synthesize the students’ proposals into an overall plan, taking the best elements from each.

The whole project is expected to cost around $5 million. Dr. Michelle Fontaine, the historical society’s secretary and grant writer, has applied to both of Maine’s U.S. senators for Congressionally Directed Spending, i.e. an earmark. She is also seeking other federal, corporate, and nonprofit foundation grants. She hopes that entire project can be completed in five or six years, but allows that it could take longer.

Besides looking for grants, the historical society will be holding fundraisers. They held a “Tea and Tour” at the hall in May and will hold a cornhole tournament and raffles during OakFest, on July 28-29. The raffle prizes are a recliner, a vintage snowmobile, a mountain bike, and a stay at a local bed and breakfast. The society is also putting together a cookbook of recipes new and old and historical photos and fun facts, the sales of which will benefit the restoration and other OAHS projects.

Finally, individual donations are most welcome. To donate online, visit the project’s GoFundMe page. If you prefer, you can mail a check to the Oakland Area Historical Society, PO Box 6, Oakland, ME 04963.

A room full of possibilities…

Download Full Newspaper: High Res | Low Res (Details…)

<— Previous Article • Summaries • Next Article —>

©2023 by Summertime in the Belgrades. All rights reserved.