When A Good Lake Goes Green

Drive nearby, and there will be a stench. Peer into the lake, and a foggy green color will yawn back. Plan to fish or swim or waterski or sunbathe, and there may be warnings to avoid contact with the water. And definitely don’t let a dog drink or children play in a lake that is green.

Lake access users (and their contribution to the economy) have the option to pivot to a body of water that is still clean and clear. Lake property owners, whose taxes contribute as much as 75% of a community’s budget, don’t have that mobility. What they do have is years of warnings, of research, of experience and of outcomes dealing with green lakes that can serve to their advantage.

Although lakes turning green is not a new phenomenon in Maine, it is always a jolt. Two examples close to the Belgrades are Lake Annabessacook in Winthrop and China Lake in China and Vassalboro. Lake Annabessacook in the Cobbossee Watershed, considered one of the most polluted lakes in the state, turned green predictably in 1939 primarily from municipal and industrial sources.

China Lake, 30 miles from the Belgrades, which turned green abruptly in 1986 — the “China Lake Syndrome” — mostly due to residential development, was the lake “with the most rapidly declining water quality ever documented in the State of Maine.” A lake restoration project which included the China Conservation Corps, the model for the Belgrade Lakes Conservation Corps, was established in 1990.

Not well known, the China project worked with Three Mile Lake which had experienced an algae explosion, pursued an alum (aluminum sulfate which binds the phosphorus into the lake bottom sediment) treatment and had another explosion four years later. The lesson: There was no watershed work; the external loading of phosphorus from runoff was allowed to continue.

It was China Lake that sounded the wake-up call to the Belgrades in 1994, predicting at the annual COLA (Maine Lakes) Conference at Colby College in Waterville that Great Pond would be next to go green.

The ensuing media coverage, community denial, and overflow attendance at the annual Belgrade Lakes Association meeting resulted in a cascade of positive developments, awareness, education and proactive planning for the future of the Belgrades that are in place today from the informal meetings of representatives of each of the Belgrade Lakes, to the formation of the first Belgrade Lakes Conservation Corps in 1995 under the umbrella of the Belgrade Regional Conservation Alliance (now known as the Youth Conservation Corps under the auspices of 7 Lakes Alliance).

Those early collaboration were in the days before milfoil (although in retrospect it is believed that Lake Messalonskee had milfoil by then) or the threat of more serious invasives, before gloeotrichia, before the swimmer’s itch eradication project, before any lands were preserved in the Belgrades (except for French Mountain and a small parcel on Watson Pond), before the Belgrade Lakes Golf Course, before climate change was a buzz word with weather lessons to back it up, and before any conservation organization or entity linked the lakes of the Belgrades except for the chain of water itself. The sole focus could be preserving water clarity, curtailing runoff, preventing algal blooms.

At that time turning green was something that happened somewhere else. Or did it?

In the Belgrade Lakes chain in August 1993 East Pond residents had the awakening experience of a major algal bloom and depth visibility on the lake was reduced to three to four feet. It wasn’t without prediction. East Pond was the only Maine lake in 1994 that was actually downgraded (to “poor restorable”) in the DEP’s report to Congress. It had already experienced up to a half dozen previous algae blooms. Some of the problems were identified in the Colby Land Use Survey Study conducted in 1992. But it was the seeing that made believers out of residents.

For East Pond there have followed many years of retreats, task forces, citizen inputs and problem-solving projects and finally the successful outcome of an alum treatment in 2018. (Always proactive, the East Pond Association is building a fund for a repeat treatment.)

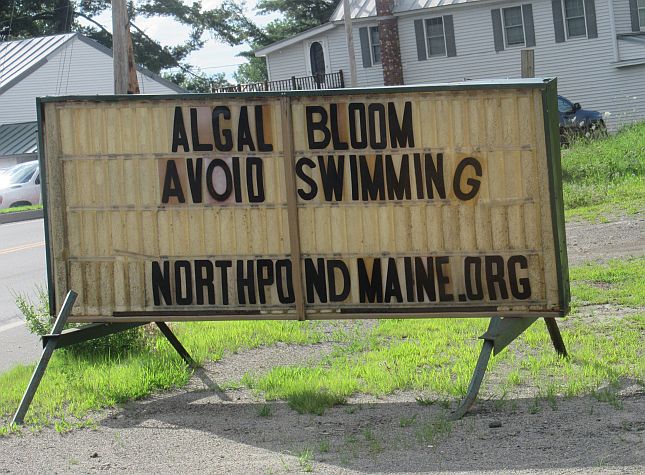

Today, the focus is on North Pond. In its seventh summer of North Pond going green, the lake association is raising money for an alum treatment. North Pond has the advantage of East Pond’s experience, of many years of scientific research conducted by Colby College and the 7 Lakes Alliance, of the examples of other successful fundraisers.

With a goal of an alum treatment in the spring of 2026, North Pond needs donations that will meet the required $3.3 million. How can everyone help? See the next article for a list of donation options.

Download Full Newspaper: High Res | Low Res (Details…)

<— Summaries • Next Article —>

©2024 by Summertime in the Belgrades. All rights reserved.